SciPy Tutorial Setup On Kubernetes

This past summer I had the opportunity to work with Min Ragan-Kelley and Matthew Rocklin on delivering a tutorial at the scientific computing conference, SciPy 2016, in Austin, Texas. We set out to teach folks generally about parallel computing in the context of data analysis and not necessarily about any one tool. That is, focusing on core concepts rather than a specific framework. There is something strangely visceral when you are first learning about distributed computation and different hostnames pop up when executing a simple map across the cluster; and to that end, we wanted to give students access to a cluster capable of doing significant work -- something more than a toy. The tutorial was well received and all the content is publicly available:

Note: these materials will also be reused in an upcoming PyData Tutorial in Washington, DC

Many tutorials can get stuck (and sometimes fail) on setup and in the post I want to describe, in detail, our solution. We drew on our previous experiences running tutorials/trainings/lectures/etc. Our goal was to give students access to a preconfigured cluster with zero entry requirements: push a button get a cluster with all tools installed.

History

In graduate school, I helped with summer workshops teaching students, postdocs, and professors about Python in the context of biophysics and complex systems. Attendees showed up with a variety of machines and OSes: Linux, Windows, and OSX (both Intel and PPC). At least a collective day was spent getting our software and materials installed on all the machines so students could get hands on experience. Often our issues were handling multiple versions of Python but also odd bugs which invariably arise during trainings: permission errors, hard drive size limits, VPN blocking...

More recently, I helped build and run a tutorial at SciPy 2013: Data Processing with Python. Each student was given access to an individual clusters preconfigured with: Hadoop MapReduce, Disco, and IPython Parallel. It was a tremendous effort to stand this up and involved piles of bash, Python, and the magic of StarCluster -- and it all had to be setup before the class started with the caveat that total provisioning took ~5 hours. Still, it worked -- though, I was exhausted.

Hello Kubernetes

Not wanting to repeat the mistakes of the past and hearing great things about GCE and Kubernetes we committed early on to the Google Cloud Platform. Generously, Google donated resources for us to build out and iterate on our tutorial cluster platform. We are extremely appreciative of their support!

"Kubernetes is an open-source system for automating deployment, scaling, and management of containerized applications." What this means, is that if you have a service wrapped up in docker image, Kubernetes can help you do a number of things: deploy the image to a machine, scale the services and load balance between N containers, and handle things like auto-restarting, rolling upgrades, and generally the management that is often involved with running larger scale web services. Additionally, the Kubernetes cluster itself is fungible -- with a few button clicks, GKE can manage Kubernetes installed on a single medium-sized instance to dozens of extremely large instances. This is especially helpful when needing to scale computing resources as demand increases.

It's worth repeating that using Kubernetes does mean buying into the container ecosystem -- in our case that means Docker.

The Sea of Containers

credit: http://panalpina.com/www/global/en/home/newsroom.html#/news/a-sea-of-containers-148839

Our goal was to give students access to a preconfigured cluster with zero entry requirements: push a button get a cluster with all tools installed. To accomplish this we need a handful of docker images:

- Web application: button and info

- Jupyter notebook

- proxy app (more on this later)

- cluster technologies: Spark, Dask, IPython Parallel

And a handful of Kubernetes concepts:

- Pods: collection of containers (similar to docker-compose)

- namespaces: named and isolated clusters

- replication controller: a scalable Pod.

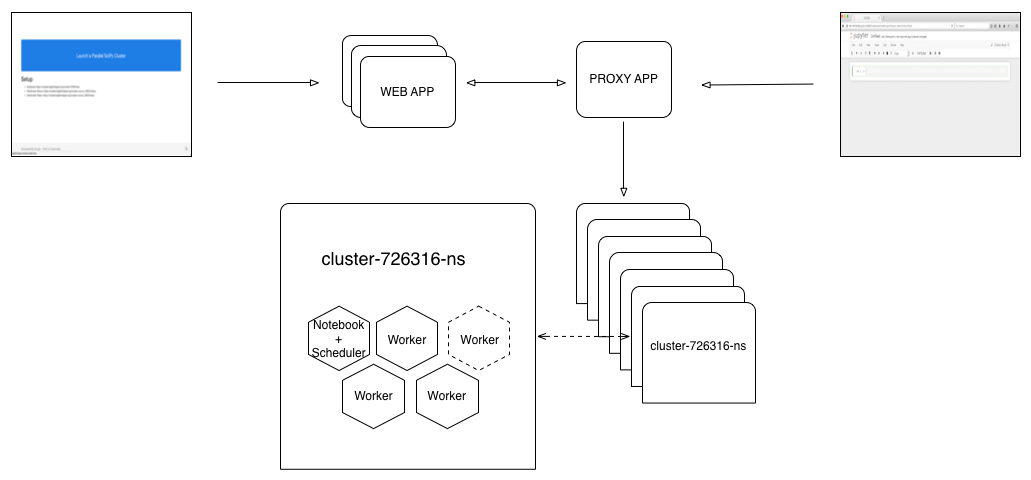

At a high level the web application launches a specific image within a unique namespace with requested resources, expose ports on the running containers, replicates some containers, and sets environment variables. And all of this, both the hardware resouces and the containers is being managed by Kubernetes. The web app is a Docker container, the proxy app is another Docker container, the namespaced clusters are a collection of Docker containers (the workers are replication controllers). It's Dockers as far as the eye can see!.

Architecture

I should also note that my friend and colleague, Daniel Rodriguez, contributed significantly to this effort and he worked out much of architecture and implementation with Kubernetes.

In building out this service we looked at previous work: mybinder and tmpnb. Both of these services launch temporary Jupyter notebooks using Docker. Similarly, we want a single page web application to launch a temporary Jupyter notebook connected to an isolated N-node cluster, where each cluster is running a variety of distributed computing engines -- also, we'd like to scale the number workers in the cluster.

The button is pushed, a cluster+notebook is produced and the user is redirected to the running Jupyter notebook.

The Proxy

When we launch a container (Pod in Kubernetes) each Pod has an internal ip but it can optionally expose a publicly available ip and set of ports. If we want to support unique clusters for each button click, we either have to generate unique public IPs and hand them back to the user or proxy to the private IPs. Since we'd like to keep everyone on the same domain, we proxy to private IPs (see diagram above). Simply, this means that when a user goes to a running notebook at https://cluster.bigfatintegral.net/cluster-678343, for example, the proxy routes to the internal container. Below is an example of routing in the proxy:

"/cluster-678343":{"target":"http://10.20.1.17:8080","last_activity":"2016-08-23T19:51:43.091Z"},

"/cluster-678343_9000":{"target":"http://10.20.1.17:9000","last_activity":"2016-08-23T18:58:26.184Z"},

"/cluster-678343_9001":{"target":"http://10.20.1.17:9001","last_activity":"2016-08-23T19:03:14.741Z"},

"/cluster-678343_9002":{"target":"http://10.20.1.17:9002","last_activity":"2016-08-23T18:58:26.191Z"}

Note, that we proxy to four different PORTs with four URL endpoints:

- /cluster-678343 -> 10.20.1.17:8080

- /cluster-678343_9000 -> 10.20.1.17:9000

- /cluster-678343_9001 -> 10.20.1.17:9001

- /cluster-678343_9002 -> 10.20.1.17:9002

Where port 8080 routes to the Jupyter notebook, port 9000 routes to the Dask scheduler, and ports 9001 and 9002 route to the Dask's web interface. All the routes can be found here: http://173.255.119.91/api/routes.

Again, much of this architecture is heavily influenced by tmpnb and uses the same proxy app -- a small NodeJS app also built by the good folks from the Jupyter team: https://github.com/jupyterhub/configurable-http-proxy .

You may be wondering how the route was registered. Service discovery/auto-registration is a bit of magic and there are handful of tools to help with this problem. Consul/etcd/Zookeeper seem to be the popular choices -- however, in our case, we opted for something small and hand built; when a Pod is launched, the startup process includes a registration script which sends a POST containing the IP and the exposed PORT of the Pod to the proxy app. The proxy app holds the data in memory and waits for an incoming request to route to.

The App

The intro to Kubernetes has the user build out a small NodeJS Docker image and a YAML file. When used with the kubectl command, the YAML file instructs Kubernetes which kind of thing it is: a replicationController, a Service, a bare Pod, what ports to expose, etc. If you are familiar with docker-compose files many of the ideas map nicely. Instead of building these files and using the command line to build a cluster we want to use the Kubernetes API. Kubernetes does not provide a language based API. Instead, they provide a swagger spec and from this, swagger can generate valid Python (or any other language) objects and functions to properly interact with Kubernetes.

# how to generate a python swagger client

wget https://raw.githubusercontent.com/kubernetes/kubernetes/master/api/swagger-spec/v1.json

brew install swagger-codegen

swagger-codegen generate -i v1.json -l python

While this code generation is a good starting point, there are no docs provided to instruct you on how to use the API. Daniel is fantastic and started the process of trial and error, eventually building up an intuition for how to navigate the code. Below is an example of how we started to understand the namespace API. We want to use namespaces for each cluster launched because we want isolate virtual clusters.

We first noted two directories: swagger_client/models and swagger_client/apis.

swagger_client/apis/apiv_api.pyhas many of the actions we want to perform with Kubernetes has andswagger_client/modelshas what looks like every model/spec for the Kubernetes universe of things. Let's look in swagger_client/models for something callednamespace. Ah! v1_namespace.py seems like a good place to start.swagger_typeslooks like the spec in a YAML file:kind: Namespace. Look at the spec in the docs -- Ok, now we'll fail our way to success -- wait! How do we create namespace? Grep inswagger_client/apis/apiv_api.pyforcreateandnamespaceand there are a bunch of functions. create_namespaced_namespace seems like a good place to start. The docstring says thebodyparam is aV1Namespaceobject so let's start building an object

class NameSpace(V1Namespace):

def __init__(self, name, proxy=None, *args, **kwargs):

super(NameSpace, self).__init__(*args, **kwargs)

self.kind = "Namespace"

self.api_version = "v1"

self.metadata.name = name

And we test:

ipdb> from .namespaces import NameSpace

ipdb> ns = NameSpace('hello')

ipdb> self.api.create_namespaced_namespace(ns)

*** core.swagger_client.rest.ApiException: (400)

Reason: Bad Request

HTTP response headers: HTTPHeaderDict({'Content-Length': '405', 'Date': 'Fri, 23 Sep 2016 17:30:04 GMT', 'Content-Type': 'application/json'})

HTTP response body: {"kind":"Status","apiVersion":"v1","metadata":{},"status":"Failure","message":"the object provided is unrecognized (must be of type Namespace): couldn't get version/kind; json parse error: json: cannot unmarshal string into Go value of type struct { APIVersion string \"json:\\\"apiVersion,omitempty\\\"\"; Kind string \"json:\\\"kind,omitempty\\\"\" } (2268656c6c6f22)","reason":"BadRequest","code":400}

It's not the most helpful of error messages -- but we keep hammering away at it until we've got the correct body contents. It goes like this until we get the

NameSpaceobject correctly setup

With a functional API we can wrap various can now dynamically construct models and build namespaces as part of a web application. Using tornado seems like a good choice here since the app is mostly idling. Let's dig in a bit to what the cluster Docker setup is made of.

The Image

Not just any ordinary docker image, this image has it all!

- Anaconda

- Dask

- Spark 2.0

- IPython Parallel

This image is the core of the cluster; responsible for running all of the distributed computing engines and environment setup. When launched as a replication controller we can scale the workers to N containers. Notice that we only have one image -- we use the same image in two modes: scheduler and worker.

Note: normally the recommendation is to run one service per docker image -- in our case, we're going to run up to four. This is ok here mostly because the intended usage is to only work with one service at a time. The various schedulers and workers are idling and not consuming many resources (mem/cpu)

The modes of the same image are differentiated by the command executed when launching

-

The scheduler command registers the container with the proxy, starts a notebook server, and starts all the schedulers for Dask, Spark, and IPython Parallel. The worker command simply starts the workers for Dask, Spark, and IPython Parallel.

By declaring the workers as replicationControllers we can scale up and down the workers in a given cluster. This is done in a single tunable parameter. During the tutorial we also used the feature to show off the flexibility of Dask; with a running cluster executing a Dask job, we scaled the number of workers to 100 and Dask happily added 92 more workers to the job to the initial 8.

Outcomes

We ran the tutorial for a class size of 100+ students and additionally during Matt Rocklin's and Jim Crist's Dask Talk. I often worry and expect things to crash spectacularly and, in our case, everything went surprisingly well! The first part of the tutorial was designed to be executed on personal machines and, as I said mentioned before, personal machines come in all varieties of OSes and platforms -- and now, including tablets! We designed the cluster to clone all of our tutorial materials from Github so students, should install problems arise, could continue following along without a prolonged time resolving setup issues.

The cluster could run cheaply with a single medium sized instance and a few minutes before students arrived we provisioned additional resources. In total, each machine could have up to 2.0 vCPUs and 8GBs of RAM or a cluster with 16 vCPUs and 64 GBs of RAM.

Kubernetes more than lived up to the hype and again, we are very grateful to the generous support from Google in helping us build and share this with the PyData and SciPy communities.