Integration Testing for the Enterprise

Building software for enterprises does not just mean more error checking (though it definitely does include that!), it means understanding a bit more about operations and IT. Each enterprise/organization has their own idea on how networking, security, authentication, and authorization are implemented; the variety can throw a big wrench in the reasonable assumptions often made in software tools deployed in those environments. It can be challenging to generalize these environments even with experiential knowledge (painful scars) and they can be even more challenging to test.

In this post, I want to tell you about a testing harness I made specifically for testing operational environments more commonly deployed by enterprise customers. As a motivating example I am going to test and validate that the package manager conda can correctly use proxies and self-signed certs.

The Problem

Proxies

If your tool/service needs to talk to the internet or generally be accessible throughout an organization it may need to use a proxy server. Proxies often act as intermediaries between a local intra-net and the global inter-net. (Late at night I think of proxies as mild-mannered pixies working at the Ministry of Regulated Communication.) In any case, many enterprise and corporate environments use proxies and thus your application will need proxy configurations possible.

Certs

Your tool may also need to download things occasionally, and that usually means

handling SSL certificates. SSL certificates are primarily used to encrypt web

traffic -- typically you see them in the URL name prefixed by HTTPS. In a

follow up post I'll talk more about SSL certificate generation. Enterprises

and their corporate intra-net, like the web at large, want to encrypt

communication across the various services and tools which operate within it.

Again, that means your tool needs to understand common SSL operations.

Solution

The good thing, of course, is that we don't have to build this all from the ground up -- someone else has already implemented all the technical bits, and your tools simply need to be configured appropriately.

In the case of conda, for example, handling proxies can be done in one of two

ways: through a setting in the configuration

file or with the common proxy environment variables

https_proxy=proxy_url:port and https_proxy=proxy_url:port for the proxying

of encrypted and unencrypted respectively. Conda knows how to handle

proxies because Conda uses

requests

which knows how to properly handle proxies.

Similarly, Conda can use and validate encrypted communication with SSL certs with a configuration setting; it passes that info down to requests, and again, requests knows how to ssl verification

And if we dig deeper, requests can do it because urllib3 implemented SSL verification which in turn is dependent on pyopenssl. But now we are out of scope. The point here is that your new tool probably doesn't need to worry about all this because someone else did 99% of the work. What your tool needs to do is be configurable for these different communication patterns -- and that brings us to the test.

Testing!

We want to test the following:

- conda install pkg behind a proxy

- conda install pkg with a custom ssl cert

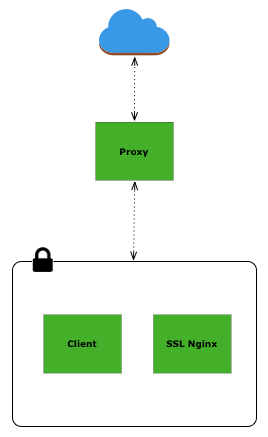

The network above is a good illustration of a proxied network. We could build this network on AWS or any other cloud provider. I've found this fairly time consuming -- I'm not un-experienced when it comes to AWS, but I have trouble keeps VPC settings in my head and I will invariably mess up the the port routing in the security groups. Still, it's an option, though you do have the added burden of managing more machines and of course paying for the use.

Instead, we could reproduce this network not with cloud based machines but with Docker based containers. This has the advantage of not having to keep track of more AWS instances and its free of cost. Using docker also has the added benefit of being easily integrated into continuous integration tools like TravisCI

Proxy Testing

Since Docker 1.9, users have been able to define custom networks for the

containers to exist in. What this means is that we can build containers in a

network which is unable to communicate with the outside world. Below is an

example of creating an isolated network named inside:

docker network create inside --internal --driver=bridge \

--subnet=192.168.99.0/24 --gateway=192.168.99.1 \

--ip-range=192.168.99.128/25

The key flag here is --internal and it disables communication between the

containers and Docker's bridge to the host. Another interesting bit to note

about Docker is that existing containers can be connected/disconnected from

existing networks. So we can build three containers -- proxy, client, and

ssl nginx -- and connect them all to the inside network; then connect the proxy to

Docker's bridge network. The proxy container will then have access to the

inside network and containers ssl nginx and client, as well as the

outside -- hey that's exactly what a proxy does!

In the proxy container we use the tinyproxy proxy and prepopulate the

config to allow the other containers. For our proxy test with conda we defined

the environment variables https_proxy and http_proxy to

install new conda

packages

SSL Testing

Testing SSL verification with conda takes a bit more setup. We are going to

need a DNS name, a webserver, some conda packages, and of course a valid cert.

Luckily, Jamie Nguyen has a great guide on issuing

custom

certificates and I essentially used his method to build a cert for the DNS name

proxy.io. To fake the DNS lookup I modified the

/etc/hosts file with the IP of the SSL Nginx container. Great, so we have

a valid dns name, a valid certificate for that name, we have the conda

packages downloaded using the proxy method, and now we just need to serve them

up.

To serve conda packages, we index them and start a server with

python. Then we use nginx as a reverse proxy to that simple server and redirect

all communication to https: nginx conf

file

With a proper condarc

file the

client container can now install conda packages served over SSL on the SSL

nginx container.

Conclusion

Testing software for enterprise configurations is possible and painful. It's painful because of the variety. I've found that Docker helps to mitigate that pain -- it's is flexible enough to handle the variety and easily integrates into larger testing harnesses. As proof, the full setup of the conda example describe above is hosted on github complete with continuous integration with TravisCI